Online and Offline Protest Participation: An Empirical Analysis for the 2020 Black Lives Matter Movement

--Work in Progress--

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, was arrested in Minneapolis. During the arrest, police officer Derek Chauvin immobilized Floyd by placing his knee on Floyd’s neck for more than eight minutes, ignoring Floyd's complaints about not being able to breathe. Floyd was pronounced dead an hour later after being transferred to an emergency center.

Images of the incident rapidly circulated through social media, leading to widespread protests against police brutality and racism. These protests soon became "the largest movement in the country's (US) history" (Buchanan & Bui, 2020), with an estimated 15 million participants. The protests revitalized the already existing Black Lives Matter (BLM) organization. Achievements in the wake of the uprising included budget cuts of $150 million to the Los Angeles Police Department and the establishment of the Black Lives Matter Plaza.

The BLM protests marked the beginning of a new era in online activism (e-activism). A historical maximum of nearly 9 million users tweeted about the movement during the protest days.

How does protesting behavior interact with the underlying Twitter’s social networks?

Often, literature has broadly focused on the effects of social media on online activism. The link between offline and online activism remains underexplored, largely due to the scarcity of data that bridges both worlds.

I used Twitter’s API v.2 under the Academic Research license to obtain my Twitter dataset. This newly created track provides access to historical and global data for non-commercial use. All data collection was performed using the twarc2 Python function. Needless to say, all data collection adheres to strict confidentiality protocols and is conducted solely for research purposes.

I present a unique dataset of Twitter users who attended some of the Black Lives Matter demonstrations in the US. I developed a classification algorithm trained on self-classified tweets, capable of predicting users' participation in protests based on their declared information together with additional metadata. This approach enables the tracking of all the online behavior of an individual up until the protest day. The combination of individual media exposure with physical action relates closely with various strands of literature, such as the role of social networks in protest participation (Larson et al., 2019) and the impact of protests on political outcomes (Acemoglu et al., 2018).

Related works

The recent availability of social media metadata has led to numerous empirical studies aimed at understanding its impact on political outcomes. Examples of research questions addressed include foreign influence campaigns (Alizadeh et al., 2020), ideology analysis (Barberá et al., 2015), and public opinion diffusion (Gorodnichenko et al., 2018).

A segment of the literature has focused on the predictive properties of Twitter usage for protest occurrence and participation. For instance, Acemoglu et al. (2018) used Twitter data to estimate the impact of the Tahrir Square protests on the rents of politically connected firms in Egypt. My paper shares similarities with Larson et al. (2019), who relied on geospatial metadata to identify protesters at the Paris rallies following the Charlie Hebdo terror attack. However, I demonstrate that Twitter's geolocation field can be misleading, as users can tag pictures with a location without being physically present there.

Classification issues

Twitter provides useful metadata, including geolocation information, time of tweeting, media attachments, content, interactions, etc. Intuitively, if we could monitor user activity before, during, and after the protest, we could identify individuals who physically attended the protest.

I created a unique dataset of users who explicitly stated their protest attendance. These self-reported tweets are highly reliable indicators of physical presence. Using these labeled tweets, I developed indicators to identify attendees of BLM marches. An algorithm trained on this labeled data can generalize this classification to the broader Twitter population, bridging the gap between online activity and physical protest participation.

Illustration of the classification for Washington DC.

Some descriptive statistics:

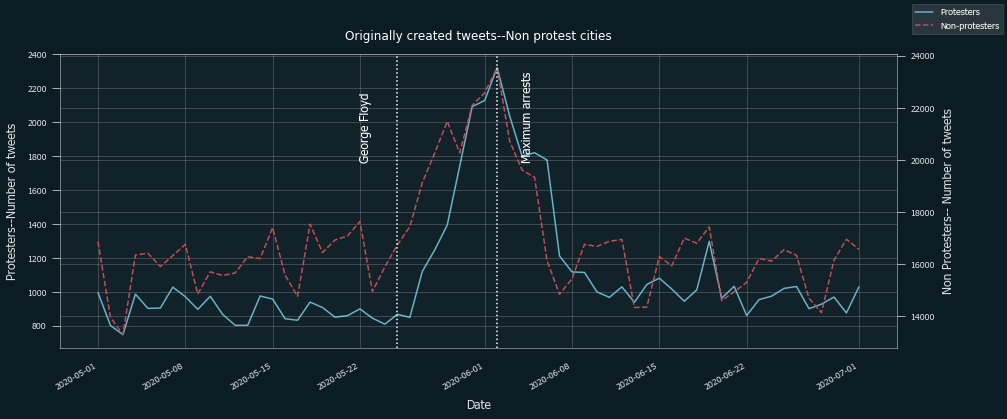

The figure below shows the evolution of tweets self-written (i.e. not retweets or mentions) for the two groups, protesters and non-protesters.

Perhaphs surprinsingly, one can see how the George Floyd's killing constituting a sudden break in Twitter activity for both groups. The maximum

number of tweets coincides in both cases with the day with more arrests overall and thus maximum turmoil.

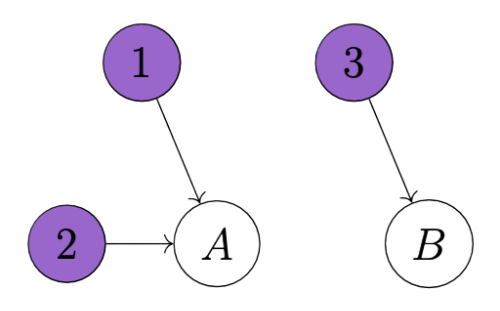

We also explore different coordination patterns joining people based on their conjoint retweeting activity. In particular, we define connections between individuals based on whether they retweet from the same users or not: Two users share a connection if they retweet from the same user at least once:

→

→